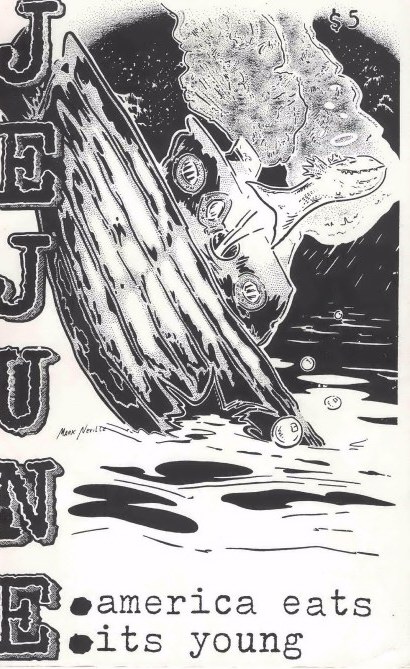

JEJUNE8

Excerpts from JEJUNE #8, Winter 1998

|

I belong to a land I have left...

-Colette

JEJUNE: america eats its young

issue #8 = WHY NOT?

US$5 per issue/ 75 Kc in Czech Republic

editrix: gwendolyn albert

managing editor: vincent farnsworth cover art: mark neville

special thanks for moral support: jules mann, sarah klein

checks payable farnsworth; back issues available:

#7--robert bly/art in former ussr/translations/montage

#6--lydia lunch /czech art/eileen myles essay/hirschman

all rights retained by artists/authors. submit!

PO Box 85, 110 01 Prague 1, Czech Republic

an interview about holocaust coverups & Romany resistance

in the Czech Republic ///with Gwendolyn Albert

former dissident & new human rights commissioner against the new empire in town

all quiet on the western fringe (rant)

fiction (x 4):

big andy butters by leanne grabel

mary ann by billy stanley*

jerri by theodore schwinke

latrell by don chase

poetry (WHY NOT?)

john wall barger

dave brinks*

john terry cooper*

dennis formento*

christopher jones

jason lynn

jenny smith

(*new orleans folk)

From a WW2

concentration camp cover-up

to post-'89 skinheads

& the Romany (Gypsy) situation

before and since

American writer Paul Polansky and Czech Romany activist Lubomír Zubák worked together in 1995-1996 collecting the oral histories of Romany survivors of the WW2-era concentration camp near the Czech town of Lety. In addition to denouncing two surviving guards from the camp for war crimes, Polansky and Zubák both maintain that the memorial unveiled at Lety in 1995--which exists largely because of the publicity brought about by Polansky's research--does not comply with the Helsinki Accords. Among other things, a pig farm built on the former campsite is still in operation and the memorial is not adequately marked for public access.

While Polansky's background information on the camp comes from the state's own archives, few journalists here have shown interest in verifying his claims through their own investigation, tending to dismiss the significance of Lety altogether by insisting that previous writings on the subject have already covered all important aspects of the story. Prior to the June 1998 elections, then-Minister without Portfolio Vladimir Mlynáø declared that he would devote himself to removing the pig farm from Lety; he soon found himself the target of a parliamentary oversight committee investigation.

The 1998 publication of Living Through it Twice (GplusG Publishers, Prague), a book of Polansky's poems based in part on the Lety survivors' oral histories, was greeted with haughty dismissal here. Some critics said these pieces aren't really poetry, or that Polansky is prone to exaggeration; others questioned his motivation and accused him of, at the very least, a particularly American naiveté. One thing is clear: the historical issues raised by Polansky's publicizing of the Lety affair have yet to be addressed in depth by any Czech journalist. This seeming indifference to the history of fascism in these parts comes at a time when incidents of skinhead violence have reached an all-time high in the Czech Republic.

Polansky's Czech publisher is Fedor Gál, a well-known former dissident committed to keeping the Lety story alive. In 1997 Gál's publishing house, GplusG Publishers, issued a Czech translation from the German original of Markus Pape's history of the Lety camp, A Nikdo Vám Nebude Vìøit (And No One Will Believe You). GplusG has recently put out another Polansky book dealing with Lety, a collection of survivors' oral histories entitled Black Silence (Tíživé mlèení).

In the following conversation, conducted in English in October of 1997 in her Prague living room, with the noise of traffic and loud drunks straggling out of the UZI bar filtering up from busy Legerová street, Gwendolyn Albert asks about what lies behind present-day Czech treatment of both the Romany minority and their own history. This interview was first published in an unannotated form in issue #22 of Left Curve magazine.

Gwendolyn Albert: You claim there was a "cover-up" about Lety coming from President Havel's office when you first publicized your discovery of this Czech-run concentration camp in the US. What does that mean?

Paul Polansky: The Czech Embassy invited me to Washington to form a historical commission and I started to smell a fish when I said: look, let's not put the commission on the documents, because they've been there for 55 years and they'll be here for another 55 years. Let's try and find the survivors, because they have a bad habit of dying, and let's try and find them before they die and get eye-witnesses to what really happened there. They said, "Fine, great!" --and when I called them back a couple of days later they started to hem and haw and said that Prague didn't think that was such a good idea.

they were told not to let me in

|

It's very easy to find anybody in the Czech Republic, because the police have a central computer with everybody's name in it, and their birth date and if they've died, their death date. Since I had a list of 1300 people that were in Lety, with their birth dates, I knew we could find any of them through the police computer. So then I asked President Havel's office if he would help me find the survivors, was he aware that war crimes had been committed at Lety, what was the Czech government going to do about it?

President Havel's office suggested that I go meet Dr. Josef Havlas at the Foreign Ministry. Well right away, I felt like: Why is the President's office sending me to the Foreign Ministry? They should be sending me to the War Crimes Commission, or to the Ministry of the Interior.

When I got to the Foreign Ministry, Josef Havlas said that he personally had been required by the President's office to investigate Lety, and he had, and he had found that it was a very small camp with "only" six guards, run exclusively by the Germans, that the only people who died there had typhus, and he had checked the police computer and there were no survivors and none of the guards had survived either -- everybody was dead. And I said, "But some of these people were only born in 1930 or '34 or '38, they were children in Lety, some of them must still be alive." He said no, he'd investigated thoroughly and everybody was dead.

G: And did he offer you paper evidence at all of this?

P: No, but he said he had been to Tøeboò [the state archive], and he had investigated personally. So the next day I was in Tøeboò, and right away, they wouldn't let me in. I have been working there since 1971, and they had orders not to let me back in.

G: Describe to me what took place.

P: Well, the reading room director was a very dear friend of mine. Every time I came to work in the archives, which was two or three times a year, I would rent a room from her father, and in the evening I would go out with her husband and with her, and we were very close friends. Once she went to visit cousins in Minnesota and she came and spent a couple of days with me in Spillville, Iowa. I mean, we were really close friends.

Well that day when I walked in and she saw me, she just turned white, and she said "Mr. Polansky, I'm sorry, but I have orders that you are not to work in this archive anymore." And I said, "Can we have a cup of coffee after work to discuss this?" and she said, "No, I can't ever see you again," and I said "What's happened?" and she said "Please, please, I can't talk to you."

Czech guards from Lety were sent to work at a new Communist labor camp

|

And so I left, and I called up my Czech cousin who used to do a lot of research with me and who was very close to [the reading room director] also, and I said "Do you know what's going on?" and he said, "Of course I do. She almost lost her job. This guy came down from the Foreign Ministry with a crew, they threatened everybody with their job and their pensions, they said they were all going to go to jail, they had a reign of terror there for two weeks," and they told them that if I ever came back they were not to let me into the archives.

G: What year was this?

P: September 1994. Now since we started at the President's office, I had to believe that everything originated back in the President's office. Maybe President Havel himself doesn't know what's going on in his own office. That's quite possible.... All of the legislation to build these camps was proposed before the Germans ever invaded. And all of these camps, without exception, were run by Czechs. The Germans were not involved, not even in the department that oversaw all these camps. No German guards, no German camp commanders, no Germans in Prague even in the section that these camps were run from.

G: So who were they exterminating?

P: They were getting rid of --

G: Anyone who wasn't Czech, or --

P: No, no, there were a lot of white Czechs in these camps. People who were against the system, people they didn't trust.

Lubomír Zubák: Homeless.

P: Homeless, orphans, mentally ill, Romanies, Jews -- anybody who did not fit into their system, or who they were suspicious of, they sent to these camps.

G: How is it possible that this part of Czech history has been so overlooked for so long? This is such a small place, and the whole world passes through here! It's not just a matter of archives - - if all these survivors exist, you would think that this information would have gotten out, maybe not in the West, but --

P: Well, in 1945 the information was getting out. There were actual investigations, government investigations about Lety and many of these other camps. I interviewed a Lety survivor who was visited by the police in 1946 to ask him and his mother and his family what went on in Lety during the war. His mother was afraid to say, but he said, "I'm not afraid to say! That camp was run by the Czechs! We didn't see one German there!"

So they started an investigation about Lety and the other camps. In 1947 the police came back and arrested this guy and took him to jail, and he was in jail for five years because he would not say that the Germans ran the camp. By this time the Communists had taken over the government, and they were starting up new camps just like Lety... guards at Lety were sent to the new camp at Jachymov, and you have the whole thing all over again. The Communists weren't going to denounce the WW2 camps because they were using them.

L: In June [1997] the War Crimes Commission came to my place looking for Paul. They asked me why we are doing these kind of things.

G: They came to the house? They didn't write you a letter?

L: No, they just drove up and knocked on the door. They told me I had to come to their office in Prague and "explain" everything. And I said, "What about the criminal? Did you go there already, to see him? Did you ask him some questions? Has some action been taken?" And they said, "We went there but he kicked us out."

G: "He kicked us out?"

L: Yes. That's what they said to me. "He doesn't want to talk to us, he refused." "So what do you want from me now?" I asked them.

G: They didn't subpoena him or anything?

US holocaust museum

turned away

|

L: No. But I agreed to go to their office, and then I started to think about it, why? Because the way they did this, coming to the house with no warning, is how the StB [the Czechoslovak Communist state security agency] used to act with me. When I got to Prague, I went to the section and said, "Please send me a normal invitation. You know where I live. I must have some proof that the War Crimes Commission is investigating this, after all, I am in contact with other Nazi hunters all over the world and at some point I will need to prove that this office and I are working together." "No, no we can't do that, but since you're here, please come talk to us." "Not unless you will give me a copy of a transcript of my statement." So they agreed to do that.

P: And all of the questions were about me: how did he meet me, how did he know me -- nothing about how he found the war criminal, it was all about how he found me!

L: Yes, exactly. So when we were done they had the transcript and they asked me to sign it. And I said "Where is my copy?" And they told me I didn't have the right to have a copy of my own statement. So I went to see the Deputy Director to demand my copy, and he told me that I had refused to cooperate with them. So I told them to destroy my statement if that was the case. Finally I got my copy and asked that that particular captain be taken off the case if they wanted my cooperation.

G: And to your knowledge the War Crimes Commission has not investigated the people you denounced?

P: They say they have, but I can't believe they have investigated because they haven't yet asked me what Stuchlík said when I interviewed him.

G: What would the proper course of action be?

P: If I denounce a man for war crimes, they should ask me what evidence I have. They should ask about the sources of my information: what documents, from what archive, do I have copies, did I interview him, do I have a written statement -- I have all these things. But they haven't asked me for them. I don't know how they're going to find anything out.

G: Is there anyone in the government who has been willing to help you?

P: I've only found one person, the Deputy Director of the Ministry of Defense. That was after spending an hour with him to convince him that we weren't trying to create a scandal, we were only trying to find out the truth. The proof will be in the documents that we've asked for from the SS archive. Brewster Chamberlain, the archive director for the Holocaust Museum in the US, was turned away from the SS archives here. They claim that none of the records have been catalogued. Those documents have been here for 55 years and they are uncatalogued?

L: They have to "work on it." This means they are destroying the most important things, destroying the proof.

P: This is the chief SS archive.

L: Even the Germans don't have this stuff.

G: They don't?

P: No. The Germans didn't even know until this year that this archive existed.

G: How did this get out?

P: It was in the press here. Chamberlain was tipped off that it existed, he came to see it, he was refused, he went to President Havel and complained that he couldn't have access. But imagine, now I go there with my reputation and say I want to see it and they say yes! ... President Havel, when he was a dissident, was my hero. I now see Havel as a hypocrite, an opportunist, a professional humanist. He's not helping the powerless today. There are a lot of people in the Czech Republic who are going down the drain -- these poor retired people who are seeing their pensions melt down, the Romanies, the Jews. They are all being trampled on, and you don't see Havel sticking up for the powerless today. You never see him walking behind the coffin of a Romany who's been killed by skinheads. He just looks out for himself. This man is obsessed with being President and jet-setting around the world collecting honorary doctorates. He is not obsessed with helping the powerless today in the Czech Republic.

G: Obviously he has a lot of support from the status quo not to make use of his political power.

P: He could have vetoed the Czech citizenship law, or the [census] law that makes it a requirement now to state your race, like the law that the Germans used to round up the Jews. He could have vetoed a lot of things, and he didn't. He prefers to be the darling of the foreign press.

G: What do you make of the US government's statements about the Romany problem?

When I stood up to give my speech, they all walked out

|

P: Well, I was at a human rights convention in Warsaw in 1994, which was attended by government delegations and non-governmental organizations, and I sat next to the American delegation because I had several friends on the delegation -- until I decided to give a speech against the Czech government. The American delegation had seen a copy of my speech, and the head of the delegation was the American ambassador to Macedonia, and he sent word to me that they would appreciate it if I would sit on the other side of the room and give my speech there, if I had to give it. I went to the chairperson and asked her if I could give my speech from whichever side of the room I wanted to, and she said yes. So I kept my chair right next to the American delegation, and when I stood up to give my speech, they walked out, every single one of them.

So I made my speech, about how I had discovered Lety, how the Czech government in 1994 was trying to cover it up. There were many Romanies in the audience, and they all came over to congratulate me after my speech, everybody wanted a copy. The only publication in the Czech Republic that would publish it was a Romany journal that had government support in Brno.

I asked the American delegation, several members, I said, "You know, there are times when you tell me to criticize President Havel and there are times when I do criticize him that you get up and walk out on me. What's happening?" And this lady who was part of the delegation was very frank and straightforward and she said, "We just got a message from Washington that we now need Havel again for something. When we need him, you can't knock him. When we don't need him, you can knock him." And that was their attitude.

Alles klar? The English language offering at the Czech memorial for the Lety concentration camp. (Photo by Paul Polansky.)collecting a big salary in an organization. They speak out when it's safe to speak out and they shut up when the American State Department has to sell the country on NATO and expand NATO and suddenly human rights disappears, because they need President Havel to back NATO, so then they can't criticize him.

G: This is something that I have long wondered about. Who makes the decisions in these human rights organizations as to when and where to say something and do something, how much of it do they have control over, how can they protect themselves against being co-opted. Lubo, what is your experience here with international human rights organizations and the Romany issue?

L: My experience is that in so many international NGO's in this country there are so many people, Czechs and also foreigners, working on this issue of human rights, and they have different kinds of projects about the Romany issue, education, social projects, health and culture and so on, but what is a pity, for me, is that in these organizations I don't find hardly any Romany people who are working there. The Romany know, more than the non-Romany, what's going on with them. I think that for many people, Czechs and foreigners, that our issue, the Romany issue, is a big monopoly for them. I have had very bad experiences with these people.

G: Give me a concrete example.

L: For example, on the issue of this citizenship law, no one was interested in it at the time, not the NGO's, nobody.

G: Why?

L: Because people didn't realize what the situation would be like in the next two or three years.

P: It's just like the seminar that President Havel sponsored in 1996 on racism. Every speaker was white-skinned. Every speaker there said that racism didn't come to this country until the Nazis brought it in 1939. Well, the historical facts are that King Charles [IV], who built the bridge here in Prague, used to hunt Gypsies the way other monarchs hunted wild boar and deer. [President of the First Republic T.G.] Masaryk, at the Treaty of Versailles in Paris, promised that every minority group that had been born in the Czech lands would be citizens of the new country, and in the end he vetoed citizenship for the Romanies who have been here for 700 years. The Romanies didn't get citizenship until the Communists gave it to them in the 1960's.

L: The racism in this country exists since the 13th century, when we came here.

P: It used to be a common practice right up to the end of WW1 to hang Gypsies by the town gate to ward off other Gypsies, and to cut off their left ear or to cut off their nose.

L: Yes, to mark them. So the racism today in the Czech Republic and Slovakia is some kind of national and traditional heritage of these people. Human rights for the Romany in all of Europe has never existed. Only written in theory, but never in practice.

L: In Czechoslovakia in 1990 a big movement started. It took only 48 hours and all of the Romany from the whole country were gathered together. This kind of action was very dangerous for the majority and many special advisors and politicians were thinking about this. And in the Czechoslovak parliament there were twelve Romany representatives, six from the Czech lands and six from Slovakia. This kind of [Romany] action had never happened before anywhere else in the world.

Europe will have to change or it will be like Los Angeles in 1993

|

I think that this citizenship law was made especially against us because this way they could separate us, break our unity, and also because in the future we could be a big model for the other Romany in other countries, if we were a success. At that time many people were complaining about us but still, if the country had never split up, we would be in a better situation today -- you would see dark policemen in the streets, I am sure we would have lawyers already, some judges already who are Romany, because they are here, these people. But many of them first of all are ashamed that they are Romany, and the second thing is that they are afraid. Some of these Romany men or women are married to non-Romany men or women, so it's also a situation which reminds me, very much, of Jewish people at the beginning of the 1930's. These people had to protect themselves, and so they lied and said that they were not Jewish. People used to buy the birth certificates of people who had died just to get some kind of paper saying they were not Jewish. Many of the Romany people feel this way.

G: Are there any Romany representatives now in the Czech parliament?

L: No, not one.

G: And in Slovakia?

L: No. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia the situation is exactly the same as far as racism, discrimination and the neo-Nazis are concerned. In the Czech and Slovak parliaments, in the governments, there are fascists. Not so many people know this, but this racism is supported by the Czech émigrés who left, for example to South Africa, and then came back.

G: They are supporting the neo-Nazis?

L: Of course. They came back, first of all, with lots of money, but also with a great deal of hatred. They used to hate the blacks in Africa, and here, who do they find? Who is dark?

G: Many people have told me that during Communist times the direct, overt racism and especially violence were not as pronounced at all, that Romanies and Czechs worked together and they went to the pubs together, that it was a completely different feeling. Was that your experience under Communism?

L: If it were possible tomorrow to change this political system it would be my wish to go back to the early 1980s. This was a better time for all of us -- Czechs and Romanies. Even sometimes then you couldn't go to the pub if you were Romany, there were also some beatings, like guards killed my friend in prison -- but then again, nobody could go outside in the street with a whole group of Nazis or whatever and say "Gypsies to the gas chamber!" and "Sieg Heil!" and so on like they do today. The police then would just pick up all those people and good-bye, you know? I'm not saying these were great times at all, because I left anyway, but today the situation here reminds me, really, of the early 1930's, what was happening with the Jewish people. Especially this [Romany] exodus to Canada now. I don't think it will be over very soon, because everywhere, in all of Europe, West or East, there will be more and more problems about human rights. I think there will start in all of Europe a civil rights movement, like happened in Mississippi in the US.

P: But a civil rights movement is no good without the legislation that goes with it. Existing laws aren't enough to protect human rights and civil rights in this country.

L: All of the majority nations of Europe, East and West, will have to establish some legislative changes. Otherwise, I think you will have Los Angeles 1993 throughout Europe.

G: It's interesting that you say L.A. 1993 because we have our civil rights legislation, but legislation does not change reality. You've lived in the US -- is there a Romany diaspora there?

L: Yes. I have met Romanies in the US, in New York and Miami -- Hungarian Romany, Czech Romany, Russian Romany, Polish Romany who came there like 150, 250 years ago. There are many Americans who don't see us as Romany, as Gypsy but like -

G: As Latin American?

L: No, I mean something else -- like if I tell them I am a Gypsy it's something imaginary. Like from some story --

G: Like a fairy tale.

L: Yes, something that existed two or three hundred years ago. That is my personal experience, because when I told Americans that I am a Gypsy, they started laughing. And so they said to me "Can you tell my future?" Something like the American Indians, exotic. That's what we are.

G: How many Romany people here in the Czech Republic feel the same way you do and are interested in taking some kind of action?

L: I think 90% of the Romany in the Czech Republic and Slovakia feel like I do -- but to do something, this is different. These people are talking inside their homes, [but they] are afraid to go out. They are afraid to make some kind of demonstration. They are afraid.

G: So why is it that you are not afraid to be working on this? I mean, you're here, you're working with Paul -- is it your experience from the US?

L: No, even before in 1978 I was already doing something, writing open letters to President Husák and so on, but of course in the US I did get big experience about the human rights issue, absolutely. Of course sometimes there are problems there, like two or three months ago a white policemen beat this man from --

P: Haiti.

L: Yes. But then you see the actions of the officials! It was on the news, and he is now asking for compensation -- this is very important, and this kind of thing doesn't happen anywhere in Europe.

The Romany issue is not only the Romany issue in the Czech Republic, or Slovakia or Romania. This is in 38 countries in Europe. In these countries there are living about 15 million Romany people. And I don't think these neo-Nazis and nationalists can just destroy 15 million people like that (snaps his fingers). It's not so easy. Of course, this violence and these racial attacks will continue for another 25 or 30 years. Many Romanies will die. But this is the process like, again, in the US. That was the same thing. One day, it's very hard to say when.

G: One of the conditions that preceded the civil rights movement in the US was WW2. Even though the Army was segregated, black servicemen went and died in Europe. There was an enormous motivation for them to come back, take advantage of the GI Bill, and say "give us our rights."

L: But we were also, many Romany were partisans fighting against the Nazis and so on!! But after WW2 there were only about 500 Czech Romanies left; the rest of them had been killed in concentration camps. And the Czechs needed slaves to rebuild this country -- plumbing, sewage, gas lines, electricity, in the mines, in factories -- and they used us also like slaves.

G: When you say slaves, explain to me what you mean.

P: After WW2 the Czechs expelled the Sudeten Deutsch, all of the Germans who lived on the border around the country. This was in 1948. Suddenly, around the border, you had the homes of three million people empty. Well, you don't want to have no population on your borders, and so the Czechs brought Romany in from Slovakia to fill most of these homes that the Germans were expelled from, because the Czechs actually feared the Germans might come back with guns, and so no Czechs wanted to live in those homes. Once the Czechs saw that the Germans were not coming back, they kicked the Romany out of those homes and took them over for themselves, especially if they were members of the Party.

The Romany were put into the jobs the white Czechs didn't want: the chemical factories, digging ditches, hard construction, the mines. They were treated like slaves.

G: So they weren't compensated, or --?

P: Well, yes, they were compensated just like anybody but they were given the worst jobs. They were given the jobs at the petrochemical plants where everybody died of lung diseases at the age of 50. They were given the jobs in the uranium mines where the Czechs didn't want to go down in the hole. They were given jobs digging ditches and digging graves that the Czechs didn't want to do.

G: And the same is true today.

P: No, today they don't get any jobs. The Czechs bring in Ukrainians for those jobs.

G: But I have seen some Romanies working here on construction sites.

there are a lot of war criminals living in the Czech Republic today

|

L: They are from Slovakia. They are working here for 40 crowns [$1.21] or whatever per hour. But I also have to remind us of something else, with respect to after the Second World War: the Czechs brought us here from Slovakia in the name of the federation, because at that time it was still Czechoslovakia. Ninety percent of the Romany used to live in Slovakia in very hard places. For us was normal a house made out of wood 2 or 3 km from the nearest village, with no electricity, and we were used to it. For example, my grandfather was a blacksmith, and he also lived in the ghetto, outside of society. When the Czechs brought us from Slovakia they put us into barracks, like something left over from a concentration camp somewhere, near the factories. There was cold water only. Later in the 60's and 70's we were still living in these very horrible places, with no hot water and the toilet outside and so on. But in the 70's they put us in these brandnew housing complexes, for example, Chanov. These people didn't know anything about this way of life--and today those places look the way they do. But nobody asked, "Why"? Everybody said "You destroyed everything, because you are Gypsies, you don't care about anything because nothing is valuable for you," and so on. And again, it's not all Romanies who were living this way. But this was a big argument from the majority against all of us. And again, now I am going back to the Jewish people -- what happened in the thirties? It's the same.

G: So, Paul, what is your motivation? You're not Romany, you're not Jewish, you're just a white guy, you could probably be leading a perfectly calm existence.

P: When this man at the Czech Ministry of Defense asked me today what motivated me, I told him I really got motivated every time someone lied to me. I fell into the Lety issue by accident. I was working on a very big project at the time and I had no intention of getting involved in looking for survivors of a Gypsy extermination camp, no intention of writing one word about Lety. But when people started to lie to me, at the highest level of the Czech government, and thought they could get away with it, that motivated me to get involved and I just got sucked in.

Maupassant said that behind every fortune, there's a crime. The nobility here have gotten back castles and art collections and forests that shouldn't have been returned. They collaborated with the Nazis.

G: Is this collaboration a matter of record?

P: Absolutely. I have found people who worked for the nobility right alongside the Gypsy and Jewish slave laborers. They are alive today, living witnesses. You don't have to interview too many old-timers to find out what was going on.

On the other hand, you have the Czech people who are not getting back a fortune by covering this up, but who want to present themselves as victims in WW2, not perpetrators of war crimes. An awful lot of people collaborated during WW2, and their descendants are alive today, or they themselves are even alive today and they want to be seen as victims. There are a lot of war criminals living in the Czech Republic today.

G: The Czechs definitely make a great deal of their victimization. It earns them a lot of sympathy in the West. Overrun by the Germans, overrun by the Russians, the West betrayed us every time, etc. I've begun to question that more and more. Just in the little things, for example, the assassination of [Reichsprotektor] Heydrich --

P: Yes.

G: The fact that there isn't really any kind of memorial to that. He was a big man for the Czech partisans and the government in exile to have assassinated!

P: If you start to look at the assassination of Heydrich, you will see how many Czechs were collaborating with the SS. Why has this SS archive in Prague never been opened to the public? Why are they still trying to keep historians out of that archive? The people who replaced the Communists in 1989 don't want that past to be uncovered.

G: And neither does the West, it would seem.

P: Well, the West is trying to make people like Havel the darlings that brought down communism so that they can open up free market trade, so that they can expand NATO. If they don't have these people saying "yes," the markets don't open. So they have to protect them.

interview

defense, but..."

a longtime Czech political reformer speaking out about (against)NATOids,

(fraudulent) opinion polls,

(themthar) US Senators

(etc.)

The name Petr Uhl (born in 1941) is well known to those who have studied the Charter 77 circle of dissidents. A leftist reformer and student leader in 1960s Czechoslovakia, Uhl was tried along with Václav Havel (now Czech President) and sentenced to five years in prison for subversion during the "normalization" period following the 1968 Soviet-Warsaw Pact invasion. After the political changes in 1989 he continued his work in journalism, and since this interview he has been appointed the Czech Republic's Commissioner for Human Rights. This article, translated from the Czech by Gwendolyn Albert and Jan Šefranka, is reprinted with the permission of KONFRONTACE magazine, a Czech anarchist publication, where it originally appeared in their April-May 1998 debut issue.

KONFRONTACE: We are tripping along in single file towards NATO. You are one of the few people with a certain political influence who is against this. Why?

Petr Uhl: I am not against insuring collective European security. However, NATO is merely pretending this is its goal. In reality its main raison d'être is the defense and enforcement of the interests of the USA. The fact that the dominance of the US military-industrial complex in NATO is so strong is what keeps me from supporting this pact.

K: And the other reasons?

UHL: There is practically nothing threatening the Czech Republic and in the next ten years I don't see the possibility of any threat. Entry into NATO is intended to strengthen the Czech Republic's right-wing establishment, support the immutability of that regime, stir up a xenophobic stance towards the East and provoke the rise of a new Iron Curtain in Europe, which I thought had been torn down for good in 1990.

K: Why is entry into NATO presented as the only way?

UHL: Czech tradition. These "one and only correct" ways have been here since the war. [Former Prime Minister] Václav Klaus most recently based his career on this; the first [way, i.e., communism] was universally rejected and this second [way, i.e. capitalism] is his. This doesn't have anything to do with NATO, it is a tried and true method for exploiting people, manipulating them. From Stalinist times up to today politicians have persisted in the opinion that people are not capable of discerning what is in their own best interests, so they decide it for them; however, they must offer a plausible explanation for their actions. If you consider that one part of the population is anti-Russian and that it's possible to maneuver yet another part of the population into this position through the appropriate information, then what can we do? It's simple.

Our values have more in common with the Chinese dissidents or Mandela's ANC than with America

|

K: And your concept of defense?

UHL: A small professional army, which in case of military threat -- and that doesn't occur overnight -- would train the rest of the population. I prefer a militia system. Alternatively, I am for abolishing universal compulsory basic military service. Within the European framework there is no need to create something new; the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe is already here.

K: Except it's very weak. Why is that exactly?

UHL: The causes are many. Klaus's government very much contributed towards weak-ening it -- for example, they forbid the construction of an OSCE center in Prague. The Czech Republic was among those states who boycotted the OSCE and tried to weaken its power. The OSCE is understood to be a society of equals and it is partially against American interests, with the possible prospect of pushing NATO out of Europe altogether. The Klaus government was such an obedient proponent of the US in Europe that some other states feared it.

K: Let's try to turn the question around. What does the Czech micro-state offer NATO? It can't be military bravery....

UHL: That's for sure. For the Alliance it's more a question of it being advantageous to gain a strategic no-man's land for future conflicts at practically no cost. Some claim that the USA should even pay the Czech Republic for its entry. It is therefore interesting, and not quite easy to grasp, that Slovakia should have fallen out of the running of those countries waiting to enter. It certainly doesn't have anything to do with the abuse of human rights or the threat to democracy -- this question might have significance for entry into the EU, but in the case of NATO those values don't play any role whatsoever. The disqualification of Slovakia could have many causes, from the influence of the Prague political elite to personal reasons. [US Secretary of State] Madeleine Albright comes from Bohemia and she could have the same view of Slovakia as, say, Václav Havel. It is certainly advantageous for NATO to call for obedience from some of the other countries now waiting in line -- Romania, Bulgaria, the Baltic states-- by making an example of the bad pupil who has been left out.

K: So we have arrived at the "societal values" that have been harped on so many times. What does this mean?

UHL: I think we would agree on basic values better and more quickly with, say, the Chinese dissidents or Mandela's African National Congress, than with America. The European tradition is different than the American one; rather than the USA having more values, it is the other way around -- in America some values are missing altogether. The American concept of law disturbs me -- for example, the recent execution of a woman in Texas in the presence of the relatives of her victim.

the USA is worse than the USSR in regard to imposing values

|

I'm not against continually comparing values and considering them, but I am against imposing them. In this regard the USA is worse than the [former] USSR -- the Russians at times had to realize that their cultural and economic level was lower than that of some of their satellites. Americans frequently do not realize this. They impose their way of life on others and then they are sometimes surprised and don't get it when those who are supposed to receive these "gifts" don't want them. You can see this most blatantly, for example, in Latin America.

K: The North against the South?

UHL: You bet. It's the defense of American wealth against the world, it's the defense of the South against the North. That's a part of this too, but.... We may think that the access to resources, the international interdependence of national economies, the widening gap between poverty and luxury -- that this is all unjust and even that it's our fault. All the same, this is no argument against defense, against its alleged immorality, because we stole that wealth. That aspect is present, but the way out is not through disarmament. It is through a rational problem-solving approach to such problems as population explosion, ecological issues, social issues -- the concept of a continually sustainable way of life, which will force people from the rich countries to economize....

K: Why is there so little support in the Czech Republic for entrance into NATO, despite the ongoing NATO-mania effort?

UHL: From the historical standpoint, Czechs are traditionally antimilitaristic and the army has never had any prestige. Most people do not see any danger and don't want to pay the army astronomical sums of money. Even now, defense is the only department of the Czech government whose income from the state budget is steadily increasing while other departments are experiencing budget cuts. Under current economic conditions this fact is enough to drive you to despair.

Moreover, I found out how the opinion polls treat those who have an opinion on the NATO issue but refuse to take part in the polls and can't be categorized either as FOR, AGAINST or I DON'T KNOW. 6% do not participate in the surveys because they are against opinion polls. Others are not interested in the NATO issue and I would estimate those to be up to 20%. Only the rest answer the questions as either YES, NO, or I DON'T KNOW.

K: Why are they doing this campaign? Do they need to convince people?

UHL: They are only doing it to make it possible for someone in the USA to say, "Look, there's a campaign going on! The government is taking care of it. More and more people want to join NATO." This is important for those American Senators who might somehow vaguely recall their distant democratic pasts and ask themselves, "Do those Czechs really want to join NATO?" The campaign is being made not for the Czechs but for American Senators. It's embarrassing.

K: Why don't people revolt against it?

UHL: Because NATO is too far away from them. They are worried about "tunneling," privatization, drastic rent increases, increases in the cost of energy, and their own poverty. The question of NATO blends in with the overall mood of apathy and passivity. It's more interesting with the politicians -- many Social Democrats are either against it or have their doubts, but because of their positions and their obligation to the party and its leadership they pretend not to have any doubts. In contrast to the voters, the party leadership is also pro-NATOid. That points to a problem of the political culture. Of course, this is a mess -- people are ceasing to be free because of their relationship to the party. The current system of political parties strips us of our freedom.

K: Well put. Referendum?

UHL: I am all for a referendum -- even for less important issues than entry into NATO.

suffering the

alternatives:

all quiet on the western fringe

"spoken spooky tour" (a reading and the film Affliction) comes to Prague

by the editors

It's not hard to detect the more recent of the western influences in Prague. Whether it's the yellow plastic imperialism of McDonald's arches mocking the curves of the ancient stone gates that the junk food giant has currently stormed, the insistent subversion by a Westinghouse intent on firing up the old communist (and universally derided) Temelín nuclear power plant, the overnight arrival of car culture (if not yet the bigger cars themselves) with its gridlock and killer smog, the bigtime selling of the NATO military-industrial complex, or the little corner bar now covered with the free Marlboro everything--tablecloths, sun umbrellas, aprons--the onslaught from points West often confirms the worse fears of the more sensitive of the xenophobes: The American Way looks like variations on Death disguised as Freedom.

westinghouse completing the nuclear power plant and the alternistes grooving on pain and domination

|

So when the alternative artists from that general direction came riding into town, it could have been hoped that their mumblings and projections would present some response to this all. The words bizarre, spoken word, and underground advertised the evening of film and recitation held earlier this year in Prague's Terminal Bar, the same venue that helped bring punk confrontationalist Lydia Lunch's excellent program here in the past. The reading by Jack Sargeant, Mark Hejnar, and Julie Peasley, the three folks riding Hejnar's film Affliction onto a "Spoken Spooky Tour" of Europe in connection with Fringecore magazine, suffered first of all from an essential lack of authenticity. The “spoken word” turned out to be badly read text. The “bizarre” and “underground” turned out to be quite familiar (Peasley's complaints of bad counter jobs), juvenile (Britisher Sargeant's grade-school level eroticism), or just clumsily derivative ("recovering Catholic" Hejnar's standard tale of a "preacher" molesting little boys).

With the readings falling far short of introducing anything unspeakable into the realm of the spoken, it was only with the screening of Hejnar's film that the evening took a turn toward the provocative. Called a documentary, Affliction (more on the title later) is made mostly from excerpts of videos Hejnar received from individuals connected with the underground music and zine scene. It is largely a series of tweakings of genitalia, self-mortification, sex play and passing gore. There are many just plain tacky and trite elements, like the hackneyed naked lady with a snake scene, or a segment resembling a commercial for phone-sex but with a hairy man dressed in women's lingerie. Wondrous displays of editing make up some good parts, like in one music-video segment with mirrored glimpses of marching and assembly-line order culled from newsreels and children's animated cartoons, shimmering over relentlessly churning grungy rock.

While the film has many such moments exhibiting beautiful technical work by Hejnar, with frenzies of corroding images overlapping each other, it lacks any coherent point whatsoever, belying another term, documentary. What it intends to document we never learn, and it is from this void that the problems stem--or spurt, ooze, plop, and gush, owing to the film's various images of blood, feces, vomit, ejaculate, what have you. The film also has major segments featuring the lesser and more well known members (in more ways than one) of various subcultures of the United States, such as censored cartoonist Mike Diana, mass-murder fetishist Full Force Frank, post-porn performer Annie Sprinkle, self-mortifier Tom Turbo, and shit-eating punk GG Allin.

It is the random sampling of these individuals, plus the lack of conviction in the direction and editing, that add up to the film's conceptual bankruptcy. Scenes such as Diana, who is legally barred from drawing as part of his probation for an obscenity charge, videoing himself vomiting on a bible and crucifix and then sticking the latter in his anus. Or GG Allin's various machinations with crap, defecating on stage and then eating it, or sucking it out of people; or Full Force Frank's display of guns and intent to someday be a mass murderer himself. In the hands of a filmmaker with something to say, these could have been edited into something on the level of a testament. They end up a confused mass of titillating images.

so an ATF agent would make a good alternative artist

|

The aim of any documentary worth its weight in videotape is to tell a larger truth. A film called Affliction should contain some idea about what the affliction is. Plus, disturbing films can often be understood in the context of an artist's other work and explanations. Lydia Lunch's films of rape and abuse are best understood as part of her exploration of the cycle of violence in American society. Without a subtext such as this, we get a jumble of compelling images and sounds to be passively devoured by TV-heads which amounts only to another bit of meaningless cultural wreckage.

Unfortunately, neither the film's internal logic nor Hejnar himself is up to any such discourse as to subtext, context, or the by-now reactionary concept of "the point." It seems that in using the scissors--whether metaphorically in Hejnar's editing room or in an opening scene where someone is sticking shears under his own bloody eyelid--no one is using their head. When asked about the title Affliction in the post-screening discussion, Hejnar said he "had to call it something." He addressed no meaning to scenes of people hurting each other and themselves, people compulsively drawing blood or in other ways pursuing what others consider repulsive, and chose to talk of the film's production, history, and accolades (the film won Best Documentary at the 1997 Chicago Underground Film Festival.) Nothing addressed the fact that Diana, Allin and Frank are obviously miserable and tortured people, or asked why that is. Despite hard-core scenes of carnage or masturbation or whatever, the hard-core emotional or societal reality of these people is avoided; it is a film in denial.

Except for the usual physical reactions that most people experience when watching these kinds of graphic scenes, the film doesn't challenge, emotionally or otherwise, in any other way. And so the director's expertise in the shuffling of quantities defies any quality of the freedom of expression he wishes to champion. Annie Sprinkle's joyous and healthy celebration of the female body is thrown together with, and implicitly equaled to, acts of self-hatred and violence. Diana's legal case--as obvious an example as you can get of an oppressive reality behind the US's delusions of liberty--is lost in a depiction of a weirdo masturbating with a doll. What appeared to be an exploration of cathartic pain rituals by Tom Turbo is stuck next to Allin's geekshow self-bludgeoning with microphone. When avowed future spree killer Frank warns the virtual audience to stop hurting children or else the children will turn into psychos like him, the moment of revelatory pathos is lost in a pastiche of the pleasures and glory of giving or receiving pain. The film does a real disservice to the idea of a documentary enlightening anything, and can be said only to document the filmmaker's technical abilities and the footage he had at his easy disposal.

Without a guiding point, out of the film's confused mix come possible messages of trendy debauchery, self-indulgence, hip violence and domination, happy wallowing in pain, sickening equals cool, a kind of macho can-you-take-the-grossness, plus a slumming fascination with the hardships of others and the inner-city. These are hardly underground notions. There is a common voyeuristic appeal in using the awfulness of other people's existence to fill your own hollowly suburban or more-so privileged one. Far from a repressed "bizarre" impulse, it is a standard offering of American culture. It is a marketing angle easily found in-between the pages of chic magazines and throughout corporate music videos, never mind printed on the T-shirt to be seen on the streets of Prague, "Urban Reality/Total Brutality." In this way the so-called underground film is of one piece with the dominant culture of its origin, featuring the pleasure of watching carnage, aggression, and cool graphics, and results in the same psychic outcomes. It serves in the desensitizing to violence and celebration of domination that are mainstays of American society. As depicted in the film, the Frank who is exalting force would make a good agent for the US department of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, or any other state police agency. The comic strip artist's projection of bitter laughter into his drawings of abuse and infanticide recalls the Gulf War jet pilot's "Say hello to Allah" as he drops bombs onto the people below. In its encouragement of the audience to sit and groove on pain and force and power, recalling the implicit messages of a militarized society, little difference remains between the underground of this film and the uglier aspects of its overground.

All of which is of little concern to Affliction. It simply exhibits a sometimes gorgeous alteration and juxtaposition of the images the filmmaker had on hand. Whether blood and cum ejaculating on a spattered face or a woman in Sarajevo with her head blown off, they are sometimes shocking images lazily collected and expertly presented. (Not to mention the disregard that many refugees from that war in the former Yugoslavia living in Prague could have been in the audience for this screening.) Making a point about, or even caring about, how these images fit into the bigger picture or will be interpreted, or the forces behind the impulses depicted, is not in Hejnar's purview. Indeed, the main concern he expressed was the possibility of getting arrested back in the States, that American artist's hopeful path to fame and success. "I fully expect to be charged," he said eagerly after the screening. Maybe that is the real affliction.